Can AI Predict Human Behavior? Stanford Proved It Can

Researchers at Stanford ran one of the biggest tests ever of whether AI can predict how real people will behave. The question: Can language models like GPT actually guess how humans will respond in social experiments?

Professor Robb Willer and his team, including Luke Hewitt, Ashwini Ashokkumar, and Isaias Ghezae, collected 70 pre-registered survey experiments from across the United States. We’re talking 476 different experimental conditions with more than 105,000 real participants.

The experiments covered everything: political views, vaccine attitudes, moral choices, policy preferences. How people react to misinformation, what makes them want to get vaccinated.

The Numbers Are Wild

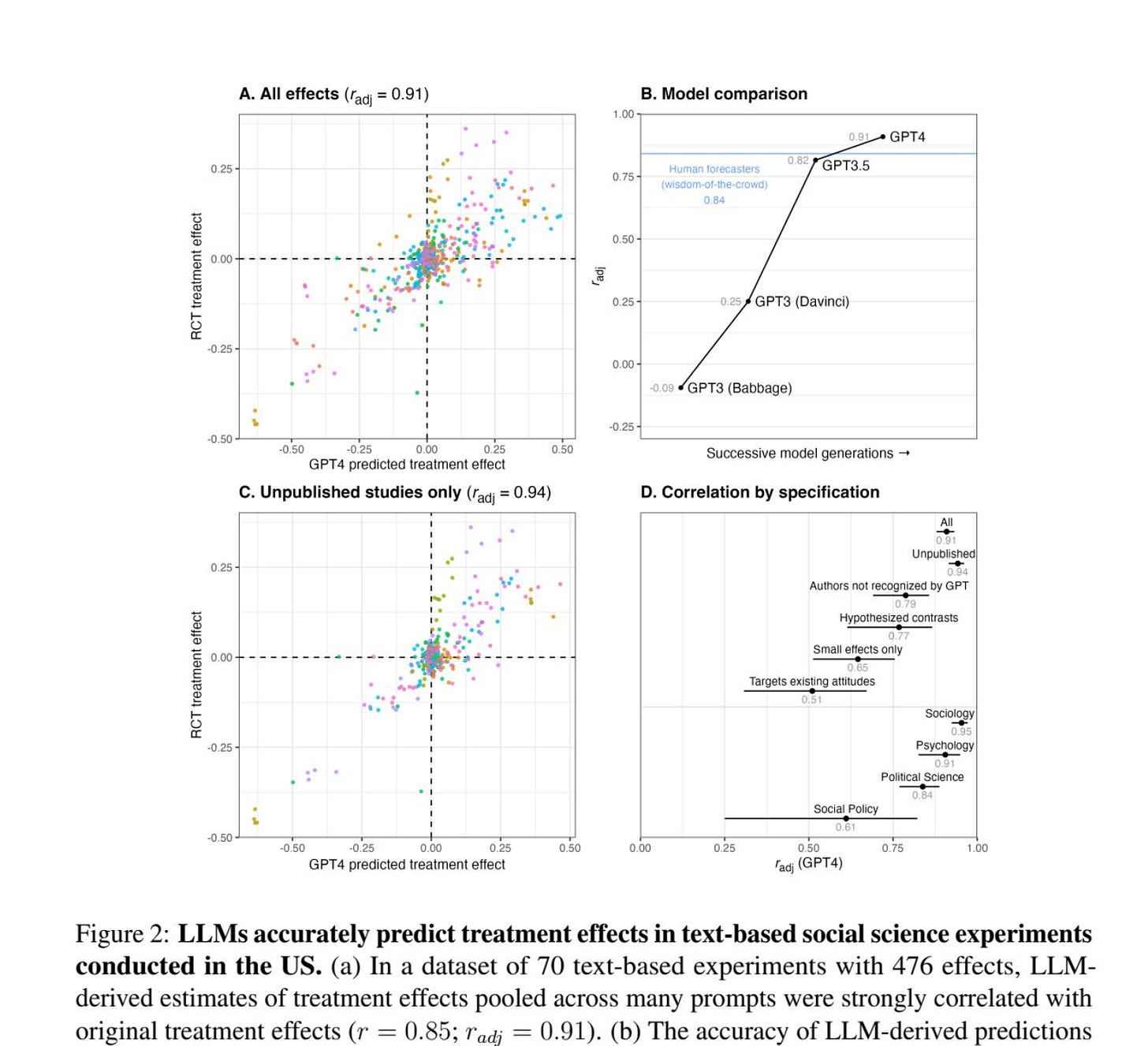

The correlation between GPT-4’s guesses and real results? 0.85. That’s crazy high for social science. But here’s what really blew my mind: for unpublished studies - stuff GPT-4 definitely never saw during training - the correlation was 0.90.

The AI predicted human responses to experiments it had never encountered with 90% correlation.

It got the direction right (whether something would go up or down) in 90% of cases. Race, age, gender, politics - didn’t matter. The accuracy stayed consistent across all groups.

It Beat Human Experts

When they compared the AI to actual forecasters and social scientists with decades of experience, GPT-4 won. Not “did about as well” - it legitimately outperformed them.

These are people who’ve spent their careers studying human behavior. They know the theories, the literature, the tricks. A language model trained on internet text beat them at predicting how experiments would turn out.

They Kept Going: The Megastudy Test

The team didn’t stop there. They added 9 more megastudies, the really huge experiments with massive samples.

Another 346 conditions. Another 1.8 million people. Text message reminders for vaccines (662,170 participants). Month-long gym attendance studies (57,790 participants).

For these bigger field experiments, the correlation dropped to 0.37. Still positive, but way lower than the survey experiments. This showed where GPT-4 hits its limits: it’s great with text-based surveys, not as good with real-world behavior measurements.

The split is clear. Survey experiments with text? Correlation of 0.47. Field experiments with actual behaviors? 0.27. Pure text interventions? 0.46. Stuff involving images, videos, or physical actions? 0.24.

The Dark Side

This ability is powerful, which means it’s also dangerous. Professor Willer put it this way:

“We also found that LLMs can accurately predict effects associated with socially harmful outcomes, such as the impact of anti-vaccine Facebook posts on vaccination intentions (Jennifer Allen et al., 2024). This capability may have positive applications, such as for content moderation, although it also highlights risks of misuse.”

Same tech that helps public health design better campaigns could help bad actors create better misinformation. GPT-4 predicted how well harmful interventions would work with disturbing accuracy.

So what do we do? Should everyone have access to this? The team actually warned OpenAI and Anthropic three months before publishing - basically saying “hey, this is powerful and could be misused.”

What It Means for Research

Running a single social experiment costs tens of thousands of dollars and takes months. Recruit people, get IRB approval, build the study, collect data, analyze everything.

Now picture testing dozens of conditions in hours for basically free:

Test intervention ideas before spending real money on human studies

Screen out harmful materials before exposing anyone to them

Perfect your messaging for health campaigns or policy work

Run pilots to figure out what’s actually worth testing

They built a demo at treatmenteffect.app where you can try it yourself. But, and Luke Hewitt was clear about this, “At the end of the day, if you’re studying human behavior, your experiment needs to ground out in human data.” The AI helps you explore, not replace actual experiments.

Why Does This Even Work?

Nobody fully knows why language models are this good at predicting people. They’re trained on internet text. They don’t experience the world.

When you adjust for measurement error (humans aren’t perfectly consistent either), GPT-4 predicted 91% of the variation in results. That’s honestly a little spooky.

Best guess? By processing massive amounts of human writing, these models picked up patterns in how we think and react. Not from living life, but from the statistical structure of how we talk about life.

But they’re not perfect. LLMs mess up “distributional alignment” - they can’t match how varied human responses actually are. Ask people to pick a number, and you’ll get wild diversity. Ask an LLM, and you get a weirdly narrow range. They flatten the messiness of real human behavior.

The Big Questions This Raises

This research hits on some uncomfortable stuff:

Does AI actually understand us, or just recognize patterns really well?

What does it mean when machines predict us better than human experts?

How much of what we do is predictable vs. actually free?

GPT-4 worked on experiments it never saw in training. That means something more than memorization is going on. It’s pulling general rules about human behavior from language patterns.

Which connects to all those debates about consciousness and intelligence. The LLM has no feelings, no self-awareness, no lived experience. But it can predict what people with those things will do.

What Happens Next

The Stanford team is clear: this supplements traditional research, doesn’t replace it. Right now, these tools work for:

Exploring ideas and generating hypotheses

Testing experimental materials as pilots

Trying out intervention prototypes quickly

Checking if content might be harmful

Tweaking message design before launch

What they can’t do yet:

Replace actual human studies for final answers

Make real policy or intervention decisions

Capture how diverse and weird human responses get

Handle culture-specific or context-heavy situations

The Weird Meta-Problem

Here’s something to think about: As LLMs get smarter and learn about this research, could they figure out they’re being used to predict humans? Could they start giving researchers what they think researchers want, like an AI version of people-pleasing?

The team calls this “sycophancy” or “accuracy faking.” As models get trained to be helpful and give users what they want, the line between real prediction and just telling people what sounds good gets blurry.

So what now?

We’ve hit a real milestone. LLMs can predict human social behavior as well as or better than experts. And it’s getting better fast.

For social scientists: huge opportunity to speed up research, test more ideas, build better interventions. But also a challenge to stay rigorous and human-centered while using these tools.

For everyone else: serious questions about privacy and autonomy. If AI can predict how we’ll react to ads, politics, health messages, what does that say about free will?

The relationship between AI and studying humans just fundamentally shifted. We’re not just analyzing data anymore. We’re simulating human experience. And nobody really knows what comes next.